Mariaz la pa badinaz, as they say in Reunion Creole. “Marriage is no laughing matter” because it’s something serious, always a little risky, one that requires a mutual commitment without which, over time, one half of the couple will ending up betraying the other.

Reunion music

The children of electro-maloya

publié par

David Chassagne

11 octobre 2023

So the first people who tried to “marry” Reunion’s traditional maloya with electronic music were met by a barrage of criticism, misunderstandings, and suspicion. Was it not sacrilege to wed earthy, organic maloya music – passed down by generations of ancestors, and using instruments made from wood and skins – with industrial, urban music that has a machine-like clinical coldness? This was ostensibly a clash between two different worlds.

However, four decades after the first banns of these unlikely nuptials were published, there is no doubt: its offspring are magnificent and creative, they’re not only grown-ups looking to the future but also remain children who respect the source, the fountainhead that sired them. Tirelessly creating new identities and breaking new ground, they shape the "Digital Kabar" – the name of a compilation album released in 2019 by the prestigious InFiné label. A term that describes an ongoing process of subtle alliances between “before” and “after” rather than just a philosophy.

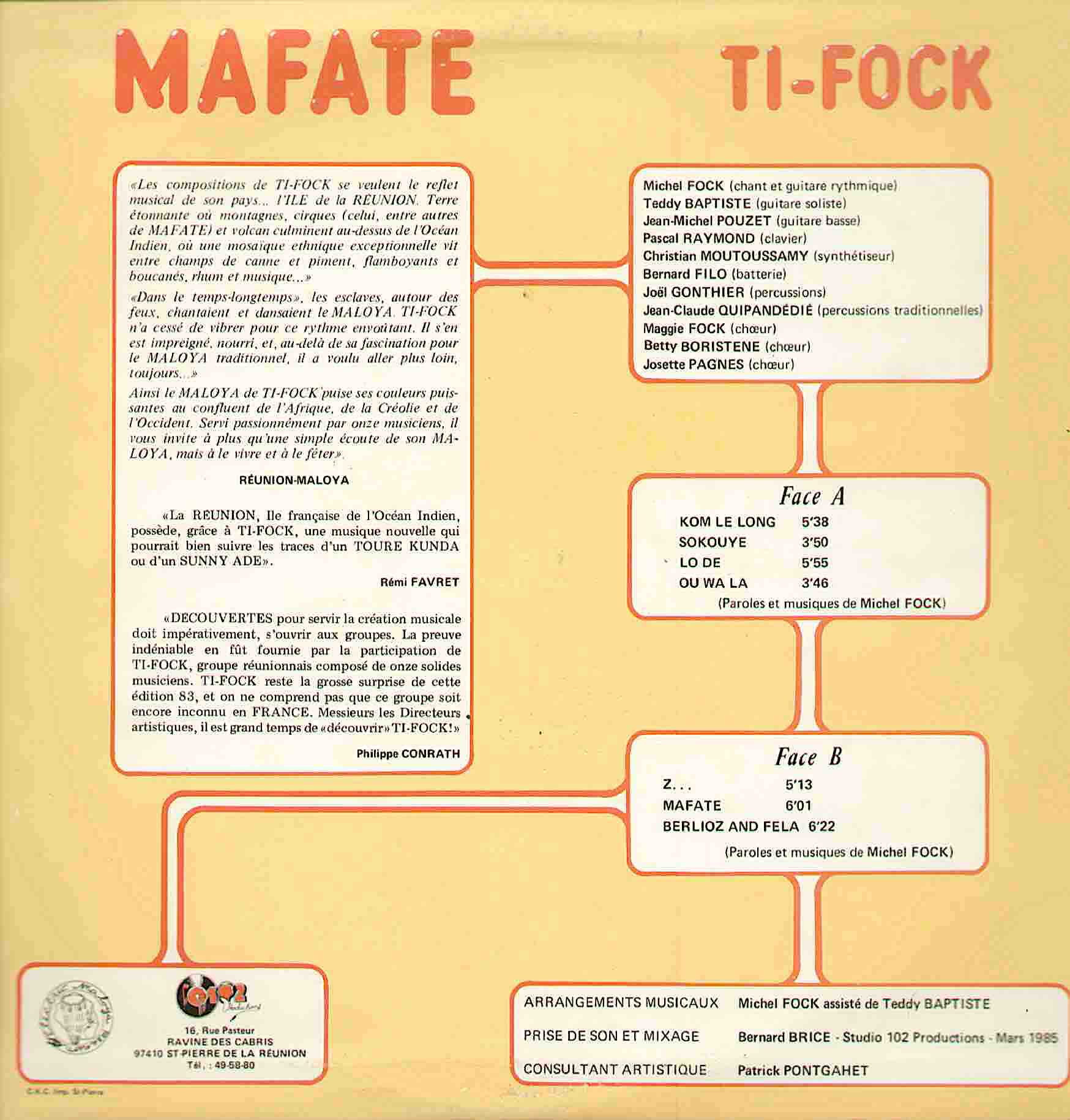

Without a doubt, the first person to broker a betrothal between maloya and techno was Ti Fock, whose father was a talented dance hall musician. As early as 1984, the artist from Reunion was featured in the French newspaper Libération, which described him as producing "ethnofuturist music", "techno maloya" and even "progressive maloya". In fact Ti Fock was simply following in the footsteps of musicians – Carousel in particular – who had already espoused maloya with rock, except that this time the instruments were no longer electric but electronic. In his sensational album "Mafate", Ti Fock included machines in a voyage of discovery that broke down barriers between jazz and latino music.

Could a rhythm machine replace Reunion’s roulèr, pikèr and kayamb (barrel drum, bamboo idiophone, and flat rattle)? The answer is clearly yes, and the 90s proved to be a decade of great experimentation. These were the “rave” years during which, on Reunion and elsewhere, clandestine parties flourished. DJs (such as L'Abuse, Nicox, Zorteil) mixed their sets with excerpts of maloya. L'Abuse, who came to the island from the Basque Country after discovering electro music in Germany, bought his first TR 808, a Roland drum machine, "for a pittance at Fo Yam", one of the few (but expensive) music stores in Reunion.

Then the first signs of a marriage of conveniences – in the plural rather than the singular – began to show, because with both maloya and electro, nothing is really reasonable or reasoned. One of the main things that links the two types of music is rhythm-based trance: binary for electro, ternary for maloya, but in both cases a call inciting body and mind to go off the deep end. But we will come back to this later. Because another thing that links them is rather more “political”. Until the 1980s, maloya was seen as a threat by the authorities, considered as a vehicle for autonomist or even independence movements. While during the 90s, the authorities were suspicious of electro music – which was then called “techno” – seeing it as a vector for drugs and public disorder. It was inevitable that one day both types of "underground" music would take a shine to each other.

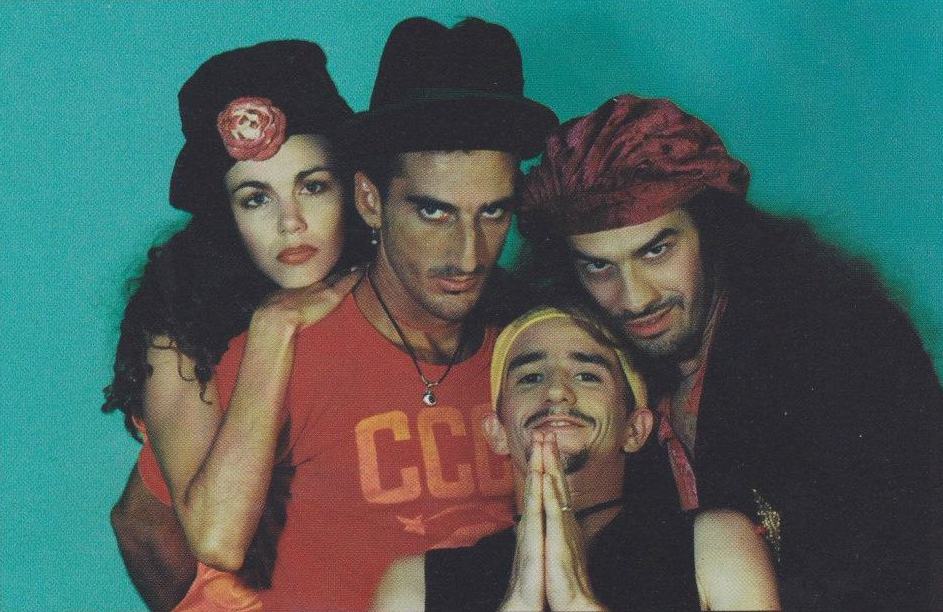

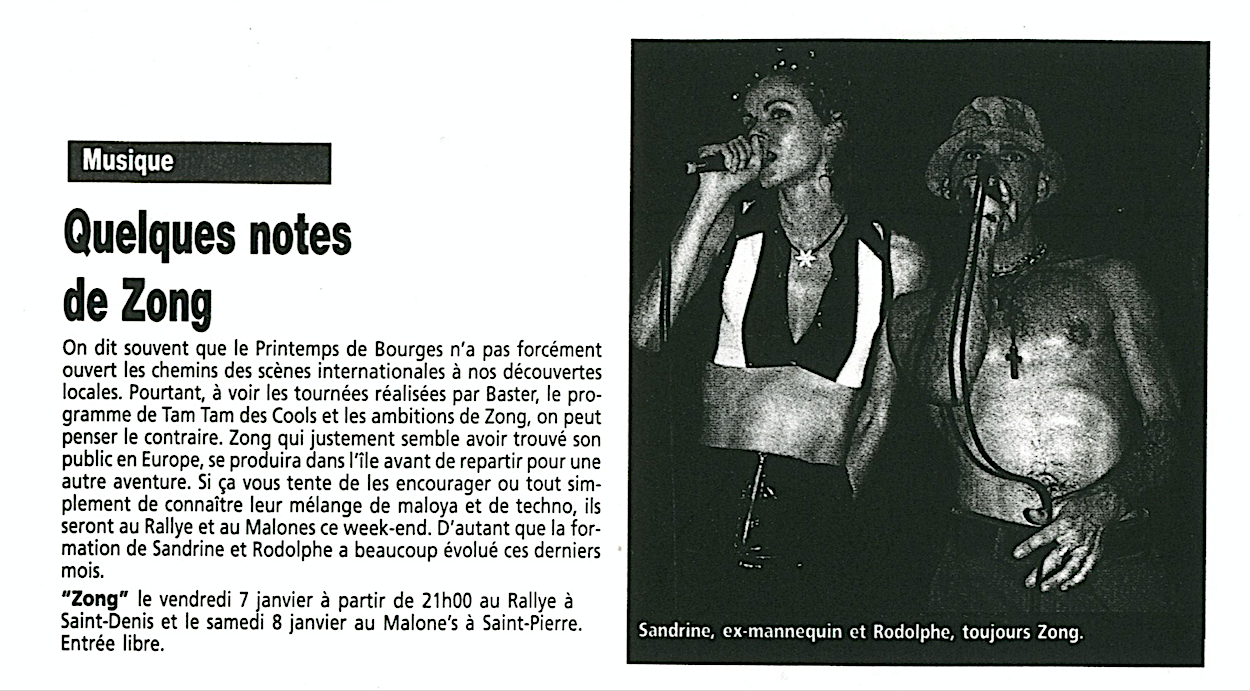

Experiments quickly ensued as digital instruments became more widely available. A cornerstone was laid by Zong, the first group to use electro as a working foundation. Whimsical creator Rodolphe "Mister Zong" Legras, and vocalist Sandrine "Drean" Ebrard were joined by a purely electro musician, Yann Costa, and drummer Cyril "Fever" Faivre. "Mister Zong" and "Drean" grew up in the bosom of Groupe folklorique de La Réunion, so séga and maloya was like their mother’s milk. This lent them all the more legitimacy to explore post-modern sounds. “We sampled our sounds in the kitchen with a floppy disk sampler,” says Drean. In 1998, Zong was selected for the Printemps de Bourges music festival, opening a new chapter.

Another cornerstone was laid by Jako Maron. Brought up on hip-hop, the artist painstakingly began breaking new ground, taking apart "organic" maloya to rebuild it into something "synthetic". Coming back to the trance state we mentioned earlier, Jako built his material around the repetition of sequences with progressive variations: the same path taken by musicians in servis kabaré (sacred rituals). The clearest illustration of this razor-sharp, fervent aesthetic research is his solo album "Saint-Extension".

Just like Jako Maron, all of Reunion’s electro musicians have not forsaken "real" maloya percussions, cooperating whenever they can with "human" artists on projects which bear witness that the marriage of electro and maloya is one made in heaven.

It would be impossible to name all the soundsmiths here, but a few to mention include the tireless Psychorigid, Boogzbrown (both members of the So Watts collective), J-Zeus, Kwalud, and the Do Moon duo. Then there’s also the Iranian Arash Khalatbari, ex-founder of the Ekova trio; based in Reunion, he fuels the fusion as much as he is inspired by it. Female musicians such as Barbee, Agneska, D-Lisha also have their place in this somewhat masculine universe. But although we’ve just travelled at the speed of light to the 2020s, a quick flashback is in order.

For towards the end of the 2000s in Rennes, a young man called Jérémy Labelle immersed himself in his father's Reunionese roots, his mother's northern roots, infused the influence of Detroit techno via his brother, and plunged into the study of musicology. He attended his First Transmusicales in 2010 before settling in Reunion to bring yet another – even deeper and sharper – breath of fresh air to maloya-electro, continuing to mix ancestral influences with unique virtuosity and an ever more precise dosage. Inspired by an era favourable to same-sex marriages, Labelle - whose EP is called "Post-maloya" – is still behind his machines, and now composes for philharmonic orchestras. He never ceases to be fascinated by the trances of grassroots "la kour” maloya.

A new generation is emerging, some of whose names we have already mentioned. To them we can also add Loya, Sofaz, Aleksand Saya... and we strongly recommend keeping an eye out for the "cartes blanches" top pick category and other line-ups at the Electropicales festival, which celebrates its fifteenth edition in 2023 and to whom we owe the “Digital Kabar” compilation. And we would be remiss not to recommend listening to the many maloya musicians who – often for quite some time already – have included electronic music without it being labelled as such: Christine Salem, Nathalie Natiembé, Maya Kamaty, Grèn Sémé … we’re forgetting some, but that's always the way of it at weddings: there’s never enough room at the banquet table!

David Chassagne

Traduction réalisée par Catharine Cellier-Smart (Smart Translate).

Picture 1: De gauche à droite, Sandrine Ebrard, Rodolphe Legras et Laurent Ladauge, Massimo Murgia du groupe Zong en 1997, Christophe Pit.