Historically, the culture of the Comoro Islands shows a strong relationship to the Swahili culture of the East African coast. Archeology, written and oral history have impressively documented these bonds dating back not less than a thousand years. The appearance of so-called twarab in the first decades of the 20th Century once more demonstrates the closeness of this cultural imaginary that links the Comoros to the Swahili world, and beyond to include the predominantly Islamic cultures of the Western Indian Ocean.

Comoros music

Mohamed Hassan and Twarab on Ngazidja

publié par

Werner Graebner

05 July 2023

The origin of Comorian twarab is closely linked to the diffusion of taarab in the Swahili world, particularly the foundation of taarab clubs on Zanzibar and, later on, the dissemination of recordings featuring songs in Swahili and Arabic. In 1908, members of the Grand Comorian community in Zanzibar had founded a musical club called Nadi Shuub, and legend has it that around 1912/13, a Zanzibar-Comorian by the name of Abdallah Mohamed Cheikh introduced the music to Ngazidja. He and a number of his disciples played the violin and the Comorians henceforth called the music by the name of fidrilia (fidla in Swahili, from the English ‘fiddle’). The exchanges expanded in the late 1920s with the movement of musicians between Zanzibar and Ngazidja, Mbaruk (Mwandjié Twabibu) and Ropiya Shenda, both of whom became famous singers during the 1940s and 1950s, are said to have come back from journeys to Zanzibar with new Swahili songs. The music took a further turn when 78rpm recordings of Swahili and Arabic songs became available in the late 1920s. By the 1930s the form—now termed ‘thouarabou’—was well integrated into the wedding customs as described in an account published in 1937:

[The] thouarabou consists of a gathering of friends and relatives at the bridal house… the groom in a cloth suit, dressed in European style, but wearing the traditional fez on his head, sits on a cushion-covered chair. … the guests crowd around in front of him. Some of them, with violins and guitars, lead the others in song. Everyone sings, swaying their head from right to left, successively, in rhythm and as one. [M. Fontoynont et E. Raomandahy. "La Grande Comore." Mémoires de l'Académie Malgache 23. Tananarive, 1937]

Twarab social clubs were launched in Moroni and the major towns on Ngazidja between the 1930s and 1950s. The period also saw the expansion of the ensembles to include—in addition to the standard violin 'ud, msondo and duf—the nai (bamboo-flute), accordion, and cello, plus a violin section of up to three players. The typical twarab orchestra of the time featured about 7-8 instruments, played by the association's members in turn. The later instrumental additions were inspired by the growth of taarab ensembles on the Swahili Coast, like the Egyptian and Al Watan Musical Clubs in Dar es Salaam, or Ikhwani Safaa in Zanzibar, and the general influence of the Egyptian firqah, via recordings and sound films. The kilabu, the club structure, was a most important element of the world of Comorian twarab, and the performance at the anda or 'grand mariage' not possible without its presence and the gamut of its offices.

Mohamed Hassan was born in Ntsaoueni on Ngazidja’s western coast in 1932. His father Hassan Mchangama headed a very religious family; his mother being recognized as the region’s best interpreter of the Quran and one of his uncles being the town’s chief Qadi. A good pedigree, but perhaps not a good starting point for a career in music, often eschewed as devil’s work among pious Muslims.

It was around 1945 when a musical group from a neighbouring village came to play in Ntsaoueni. They had one violin player, the others played ngoma [local drums]. I was so struck by the sound of the violin that I went to work the following day trying to build a similar instrument from material at hand, strings made from coconut fiber. The following year we started our own little music club, and in 1948 we gave a first public performance. I played on a violin made by a local craftsman. The concert was a big success and we continued playing at weddings. The songs we played were Swahili and Arabic songs—Swahili songs by Siti bint Saad's group, later by Bakari Abedi, all from Zanzibar, songs by the grand masters of Arabic music of the time, like Mohamed Abdul Wahhab or Um Kulthum.

At that time we did not sing in Shingazidja [the island's language]. All the songs were either in Swahili or Arabic. We copied these songs from records that people brought back from their visits to Zanzibar. After I had performed my first Shingazidja song in 1962, people came from all over the island to see whether it was really true what they had heard about. Such was the surprise at hearing twarab sung in our local language.

As Mohamed Hassan explains, songs continued to be sung in either Swahili or Arabic throughout the 1950s. Yet we have to be aware that Swahili was not just a recent import. Like many Comorians of his generation, especially in the towns, Mohamed Hassan was well-versed in Swahili. Swahili was also the literary language, the adapted Swahili-Arabic script being widely in use for literary discourse, poetry, writing letters, etc. Thus the use of Swahili in twarab would not be a simple borrowing of some imported song lyrics, hardly understood by the public, but be expressive of and reinforcing ideal and urbane language use. When in the late 1950s and early 1960s twarab performers began to produce songs in the languages of the islands it was a move linked to the general political climate, the Pan-African anti-colonial sentiments with a stress on local norms and culture, against the culture of the colonial powers.

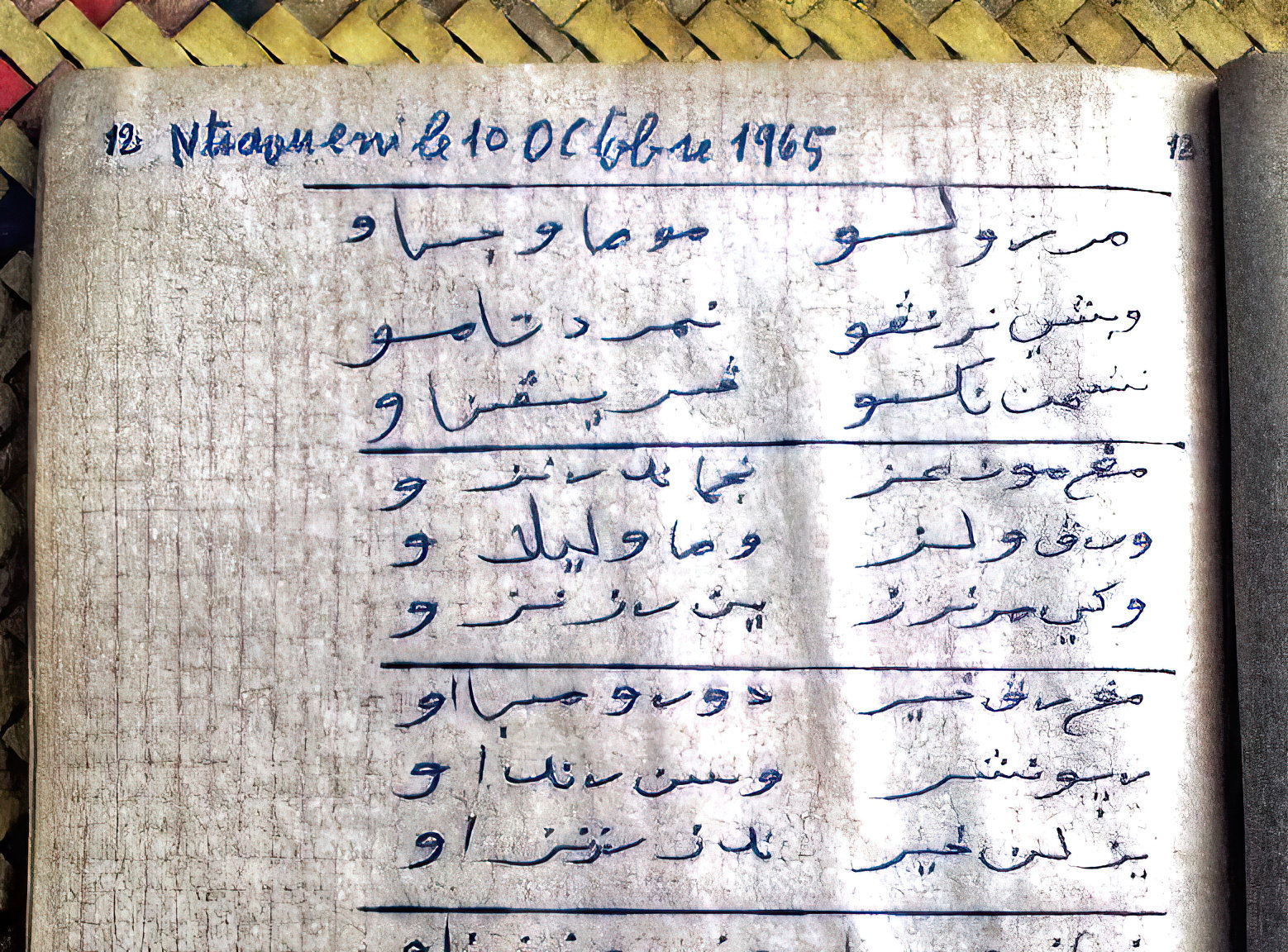

Though he is also literate in the Roman script, Mohamed Hassan continued to compose and notate all his songs in an adaptation for Shingazidja of the Swahili-Arabic script. Here is an excerpt from his song-book, Mri Uwalao (“The Flowering Tree”) :

Mri riwalao mwema udjisao (mbesheleo) The tree that we planted is a beautiful and flowering one

Upvashiya ndravu na marunda tamu Full of branches and savory fruits

Na tamani nkuu pvo riyapvunao Of great value when we harvest from it.

Mngu mwenyi enzi ndjema ndo randzao God Almighty, it is a favor that we ask

Uripve walezi wema walelao Give us parents, who are good educators

Wake warandazi ena rizandzao That they may be our counselors for all that we crave for.

Mngu ripve kheri dua ndo riombao God Almighty, give us luck, we beg you in this prayer

Ripuwe na shari usoni rendao Save us from misfortune now and in future

Yezilo na kheri ndizo rizandzao All that is good, this is what we ask for.

Besides Mohamed Hassan other champions of twarab in Shingazidja include Said Mohamed Taanchik and Maabad Mzee, the latter being the singer and chief composer for the orchestra of Asmumo (Association Musicale de Moroni), the most prominent musical club in Moroni. Asmumo's sound during the early 1960s was similar to that of the well-known Zanzibari orchestras, with a string section of violins and 'ud (lute), qanun (zither), nai (flute), dumbak (drum) and riq (tambourine). Mohamed Hassan, Asmumo and other twarab artists recorded frequently for Radio Comores, the only recording outlet in the country at the time. Mohamed Hassan had become the most famous singer by the late 1960s and In 1969 and 1972 he was invited to perform for the Comorian community in Majunga (Madagascar). On these occasions he recorded a number of songs for a Malagasy label based in Antananarivo (on a sub-label called Voix de Comores).

![Mohamed Hassan, 45rpm record cover, Voix de Comores [Tananarive, ca. 1970]](https://www.phoi.io/upload//files/543/mohdhassanvoixdescomores.jpg)

Comorian music went through a period of modernization during the late 1960s, when the introduction of a regular jazz or rock drum set made the music rhythmically more energetic and dance-heavy. Amplified lead instruments, such as guitar or organ, were needed to balance the loudness of the drums. While the earlier acoustic twarab, with its lyrics partly in Swahili or Arabic, was associated with something of an upper-class, snobbish urban attitude, the new music, henceforth called mshago, moved out into the villages, with every village soon boasting one or two rival associations and their bands. The new mshago twarab was also part of a rising youth culture that adopted the social criticism of sambe (traditional dance) songs. The final blow to the twarab of old came shortly after independence (1975) with the new regime of Ali Soilih. Under Soilih's revolutionary government (1975--78), the twarab heritage was seen as a reactionary import and nearly all the old recordings were removed from the Radio Comores library.

Like other ‘old guard’ twarab artists Mohamed Hassan stopped performing and returned to lead a quiet life in his native Ntsaoueni. He considered a comeback in the early 1980s, however, he was not prepared to make the move to the new electric and dance-heavy mshago style. In later years Mohamed Hassan occasionally accepted invitations to perform at weddings, in 1998 he was invited for a few performances by the Comorian community in Marseille, later also to La Reunion. In 2004 he was awarded a presidential medal in appreciation of his accomplishments and contribution to Comorian national culture. Mohamed Hassan passed away in his native Ntsaoueni in 2013.

Werner Graebner

Photo : Mohamed Hassan in front of his home in Ntsoueni, Werner Graebner 1998

Audio : Mohamed Hassan “Mri Uwalao” [recorded by Werner Graebner, Moroni 1998; released on: Duniya: Twarab legend from Grande Comore. Dizim Records CD 4507-2; 2000].